Transaction Verification and the Blockchain

A transaction transmitted across the network is not verified until it becomes part of the global distributed ledger, the blockchain. Every ten minutes on average, miners generate a new block that contains all the transactions since the last block. New transactions are constantly flowing into the network from user wallets and other applications.

As these are seen by the bitcoin network nodes, they get added to a temporary “pool” of unverified transactions maintained by each node. As miners build a new block, they add unverified transactions from this pool to a new block and then attempt to solve a very hard problem (aka Proof-of-Work) to prove the validity of that new block. The process of mining is explained in detail in “Introduction” on page 177.

Prioritization of Transactions and Block Creation

Transactions are added to the new block, prioritized by the highest-fee transactions first and a few other criteria. Each miner starts the process of mining a new block of transactions as soon as they receive the previous block from the network, knowing they have lost that previous round of competition. They immediately create a new block, fill it with transactions and the fingerprint of the previous block, and start calculating the Proof-of-Work for the new block.

How Does Bitcoin Mining Verify Transactions?

Reward for Mining a New Block

Each miner includes a special transaction in their block, one that pays their own bitcoin address a reward of newly created bitcoins (currently 25 BTC per block). If they find a solution that makes that block valid, they “win” this reward because their successful block is added to the global blockchain, and the reward transaction they included becomes spendable. Jing, who participates in a mining pool, has set up his software to create new blocks that assign the reward to a pool address. From there, a share of the reward is distributed to Jing and other miners in proportion to the amount of work they contributed in the last round.

Alice’s Transaction and Block Generation

Alice’s transaction was picked up by the network and included in the pool of unverified transactions. Since it had sufficient fees, it was included in a new block generated by Jing’s mining pool. Approximately 5 minutes after the transaction was first transmitted by Alice’s wallet, Jing’s ASIC miner found a solution for the block and published it as block #277316, containing 419 other transactions. Jing’s ASIC miner published the new block on the bitcoin network, where other miners validated it and started the race to generate the next block.

Block Confirmation and Trust in the Network

You can see the block that includes Alice’s transaction here:

https://crypto-guidance.com/how-does-bitcoin-mining-verify-transactions/.

A few minutes later, a new block, #277317, is mined by another miner. As this new block is based on the previous block (#277316) that contained Alice’s transaction, it added even more computation on top of that block, thereby strengthening the trust in those transactions. One block mined on top of the one containing the transaction is called “one confirmation” for that transaction. As the blocks pile on top of each other, it becomes exponentially harder to reverse the transaction, thereby making it more and more trusted by the network.

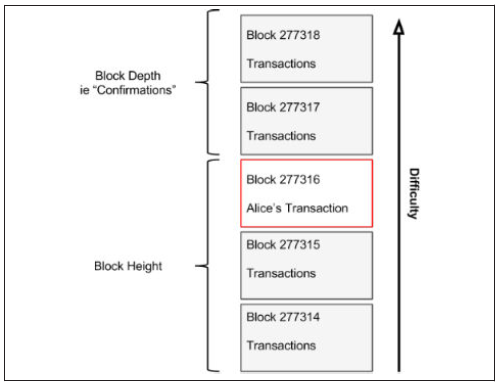

Block Height and Confirmations

In the diagram below, we can see block #277316, which contains Alice’s transaction. Below it are 277,316 blocks (including block #0), linked to each other in a chain of blocks (blockchain) all the way back to block #0, the genesis block. Over time, as the “height” in blocks increases, so does the computation difficulty for each block and the chain as a whole. The blocks mined after the one that contains Alice’s transaction act as further assurance, as they pile on more computation in a longer and longer chain. The blocks above count as “confirmations.” By convention, any block with more than six confirmations is considered irrevocable, as it would require an immense amount of computation to invalidate and re-calculate six blocks. We will examine the process of mining and the way it builds trust in more detail in “Introduction” on page 177.

Spending the Transaction

Now that Alice’s transaction has been embedded in the blockchain as part of a block, it is part of the distributed ledger of bitcoin and visible to all bitcoin applications. Each bitcoin client can independently verify the transaction as valid and spendable. Full-index clients can track the source of the funds from the moment the bitcoins were first generated in a block, incrementally from transaction to transaction, until they reach Bob’s address. Lightweight clients can do a Simplified Payment Verification (See “Simplified Payment Verification (SPV) Nodes” on page 150) by confirming that the transaction is in the blockchain and has several blocks mined after it, thus providing assurance that the network accepts it as valid.

Bob Spending the Transaction Output

Bob can now spend the output from this and other transactions by creating his own transactions that reference these outputs as their inputs and assign them new ownership. For example, Bob can pay a contractor or supplier by transferring value from Alice’s coffee cup payment to these new owners. Most likely, Bob’s bitcoin software will aggregate many small payments into a larger payment, perhaps concentrating all the day’s bitcoin revenue into a single transaction. This would move the various payments into a single address, utilized as the store’s general “checking” account. For a diagram of an aggregating transaction, see Figure 2-6.

Extending the Chain of Transactions

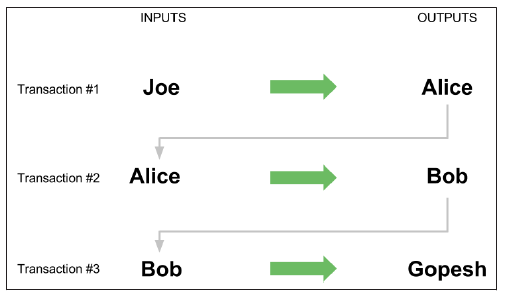

As Bob spends the payments received from Alice and other customers, he extends the chain of transactions which in turn are added to the global blockchain ledger for all to see and trust. Let’s assume that Bob pays his web designer Gopesh in Bangalore for a new web site page. Now the chain of transactions will look like this:

Ho